Reading Scripture Closer

to the Source

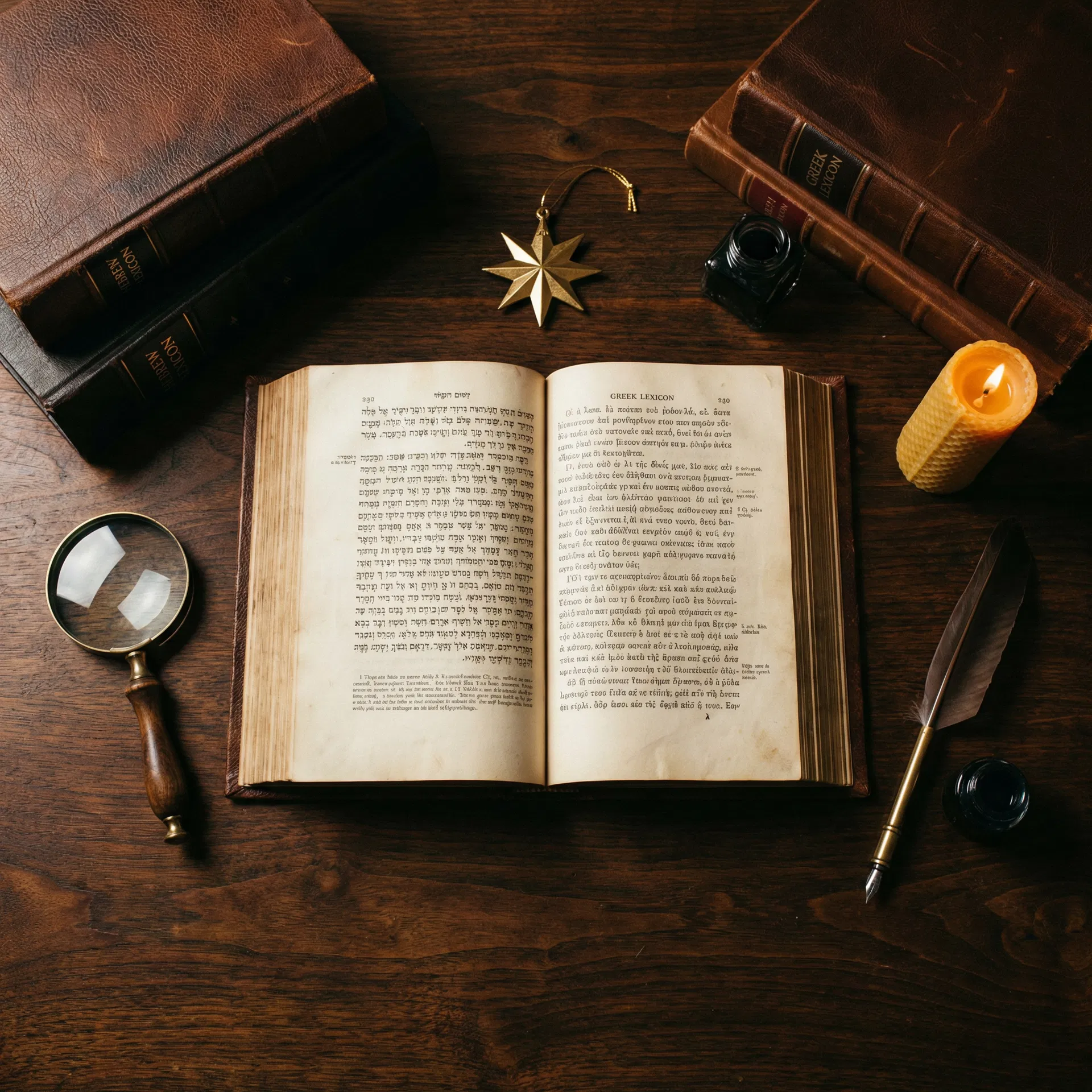

A digital repository and research platform dedicated to the original-language texts of the Old and New Testaments — Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek — organized for AI-assisted study, close reading, and cross-cultural interpretation.

More Than a Library —

An Environment for Close Reading

The Philippine Bible Project is a digital repository dedicated to the original-language texts of the Old and New Testaments — a place where students, pastors, translators, scholars, and thoughtful readers can trace words to their roots, follow themes across books, compare semantic ranges, and examine how grammar, idiom, and historical context shape meaning.

"Moving beyond 'What does my translation say?' toward 'What is this passage actually doing in its language?'"

A note of scholarly honesty matters here: there is no single surviving "original manuscript" of any biblical book. What we have are ancient textual traditions preserved through manuscripts, and the task of responsible reading includes engaging those traditions carefully. The Philippine Bible Project exists to make that careful work more accessible — without pretending that complexity disappears.

Original Language Texts

Hebrew, Aramaic, and Koine Greek manuscripts organized for systematic exploration — searchable, indexed, and cross-referenced across the entire biblical corpus.

AI-Assisted Close Reading

AI-powered indexing surfaces patterns humans miss: repeated constructions, intertextual echoes, thematic clusters, and semantic networks across corpora. A lens, not a master.

Cross-Cultural Interpretation

Bridging Eastern relational wisdom and Western analytical precision — cultivating discernment about which conclusions arise from the text versus from cultural defaults.

Formation, Not Just Information

Not merely a database. A platform that helps readers become aware of their assumptions, slow down, and read with integrity — toward renewal of mind and life.

Reading Closer to the Source

Is Not Elitism. It Is Humility.

Reading Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek — even with tools — is about reducing avoidable distortion and increasing interpretive humility. This approach supports a mature, courageous spirituality: not "reading to confirm what I already believe," but reading to be corrected, refined, and rebuilt.

See the Range of Meaning

A word can carry theological weight that a single English gloss can't hold. Reading in the original reveals the full semantic range — not just what a translator chose, but what the text makes possible.

Notice What Translators Must Decide

Tense, aspect, emphasis, metaphor, discourse flow — every translation involves choices that can subtly steer doctrine. The original text shows you where those decisions are being made.

Encounter the Bible's World on Its Own Terms

Hear its idioms, rhetorical patterns, and cultural assumptions rather than importing modern ones by default. The text's world is not ours — and that distance is informative.

Gain 'Then' Before Declaring 'Now'

Ask with honesty: What might this have meant to its first hearers? Only after that comes the second discipline: What does faithful application look like today?

"Truth withstands scrutiny, and reverence is not threatened by careful inquiry."

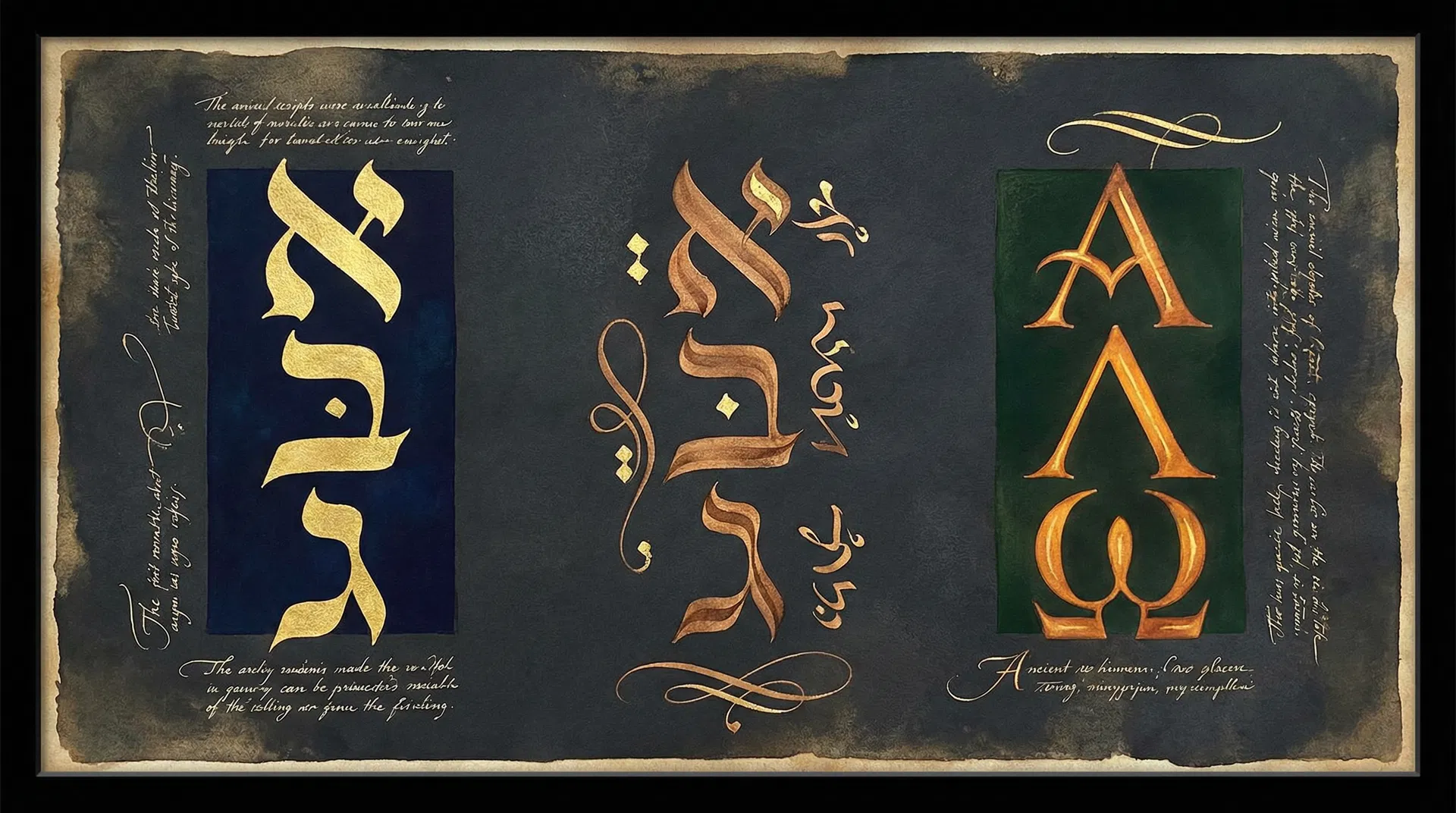

The Languages of Scripture

From a historical-linguistic standpoint: the Old Testament reflects a Semitic cultural-linguistic matrix, while the New Testament reflects a Hellenistic communicative strategy — written in Greek to scale its message across the Roman World.

Semitic Matrix

A Northwest Semitic language. The majority of the Old Testament was written in classical Biblical Hebrew, spanning roughly 1200–400 BCE in composition and compilation.

The diplomatic and administrative lingua franca of the Neo-Assyrian, Neo-Babylonian, and Persian empires. Found in:

3rd–2nd century BCE. The Hebrew Scriptures translated into Koine Greek, becoming foundational for early Christianity and the New Testament authors' primary Scripture.

Hellenistic Strategy

All 27 books of the New Testament were written in Koine Greek — the common Greek dialect of the Eastern Mediterranean following Alexander the Great. Timeframe: approximately 50–100 CE. Authors wrote in Greek to reach a broad, multilingual Roman Empire audience.

The New Testament reflects a deliberate Hellenistic communicative strategy — written in Greek to scale its message across the Roman World, while remaining deeply rooted in the Semitic cultural-linguistic matrix of the Old Testament.

The Philippine Crossroads:

Discerning East–West Lenses

The Philippines stands at a crossroads of Asian (Eastern) and Western intellectual currents, shaped by layered histories, local cultures, and global Christianity. That position can become a gift.

The Philippine Bible Project is a formation tool — a platform that helps readers become aware of their assumptions, slow down, and read with integrity. The goal is not to replace one cultural dominance with another, but to cultivate discernment.

Interpretive habits differ across cultures. Neither lens is automatically "right," and both can become distortions when absolutized. The question to ask is: are our theological conclusions arising from the text — or from the cultural defaults we brought to the text?

Western Interpretive Habits

- Systematic categories and logical frameworks

- Legal metaphors and forensic theology

- Analytical precision and propositional truth

- Individual salvation and personal faith

Eastern Interpretive Habits

- Relational understanding and community identity

- Honor/shame dynamics and social fabric

- Wisdom patterns and holistic thinking

- Collective belonging and covenant loyalty

"The goal is not to replace one dominance with another, but to cultivate discernment: to ask whether our theological conclusions are arising from the text — or from the cultural defaults we brought to the text."

Doctrine Is Shaped by

Linguistics and Culture

Doctrine doesn't form in a vacuum. It forms through interpretation — and interpretation is always mediated by language, culture, and history. A single translation decision can cascade into theological certainty. A culture's preferred categories can become "obvious" meanings even when the text is doing something else.

Language

Semantic range, syntax, metaphor, and genre all shape how meaning is constructed and received.

Culture

Values, assumptions, social world, and story-shapes determine what seems 'obvious' in a text.

History

How communities receive texts, argue about them, and institutionalize conclusions over centuries.

The Philippine Bible Project highlights this reality not to destabilize faith, but to strengthen it — because truth withstands scrutiny, and reverence is not threatened by careful inquiry. AI-powered indexing can assist by surfacing patterns humans miss: repeated constructions, intertextual echoes, thematic clusters, shifts in register, and semantic networks across corpora. Used responsibly, AI becomes a lens, not a master — always accountable to the text, to evidence, and to transparent methods.

The Spirit of Honest Inquiry

Intellectual Honesty

Naming uncertainty, avoiding forced conclusions. The text is not a mirror for our pre-existing beliefs — it is a witness that may correct us.

Textual Accountability

Showing one's work, tracing claims back to language evidence. Every interpretive claim must be answerable to the text itself.

Interpretive Humility

Recognizing limits and learning from others. No single tradition, culture, or era has the complete picture.

Transformational Intent

Not information alone, but renewal of mind and life. The aim is to become the kind of people who can bear truth — carefully, responsibly, and courageously.

May your paradigms lead to transformations.

Be Part of This

Scholarly Conversation

The Philippine Bible Project invites students, pastors, translators, scholars, and thoughtful readers to engage the original texts with honesty, humility, and transformational intent. Sign up to receive updates as the platform develops.